By leading the 1943 Rolls-Royce Hillington strike, Agnes McLean and her comrades paved the way for the feminist movement to demand equal pay for equal work.

Agnes was born on 4 November 1918, in Scotland Street, Ibrox, Glasgow into a family of socialists. Her father was a strong socialist and a member of the Scottish Workers’ Republican Party. Agnes attended a Socialist Sunday School as opposed to a Christian Sunday School, which had its own commandments in line with socialist theory.

Agnes left school in 1932 at the age of 14 and went straight to work in Collins Books as a bookbinder. After a while Collins decided to up the production rate, but the bookbinders were not afforded a pay rise. Agnes, a member of the union, having joined at the start of her employment, decided to act. Following a discussion with the hierarchy of the company, Agnes secured an increase in wages for the bookbinder staff.

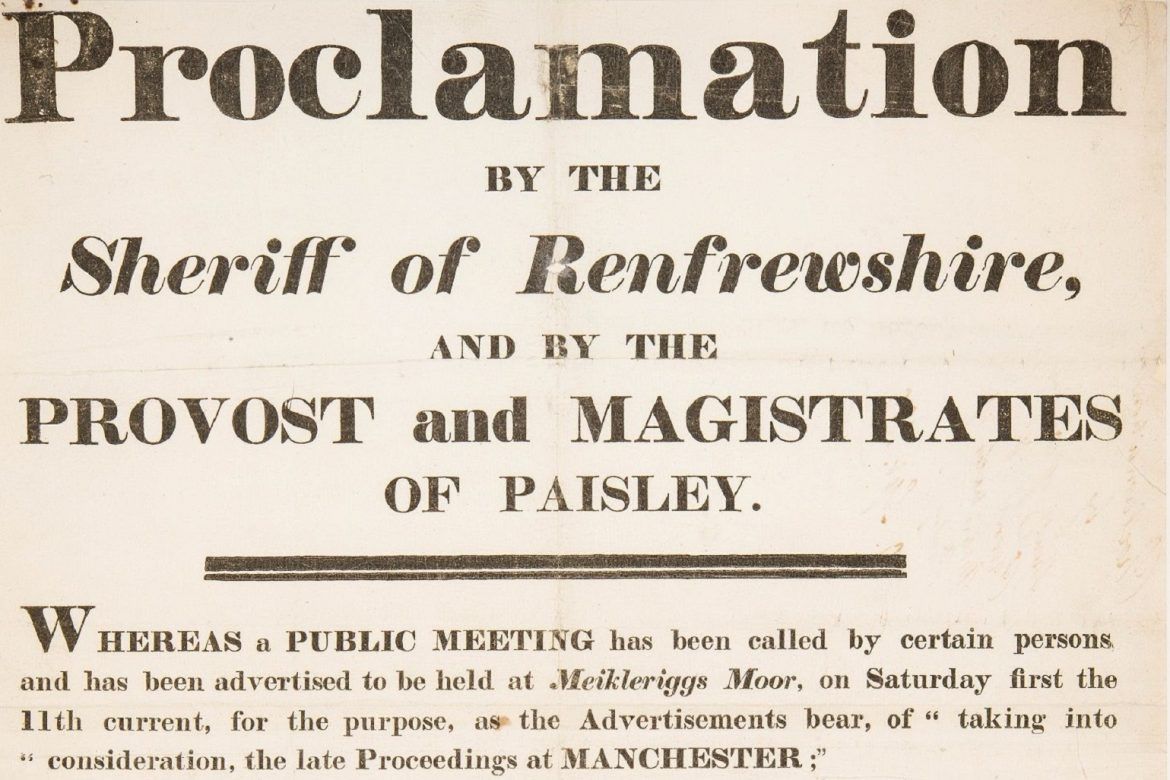

In 1937 Agnes joined the Rolls-Royce factory in Hillington, Renfrewshire, at the age of 19 as a crane driver where she joined the Amalgamated Engineering Union (AEU). The Hillington plant produced the Rolls-Royce Merlin V-12 engine, used by British fighter and bomber aircraft in the Second World War. In 1940 there was an agreement on equal pay for its female workers at the Hillington plant, however this was not held and in practice women were paid a lower grade for the same work earning around three quarters of the wages men received for the same work. In 1941 Agnes and her comrades led a strike for female recognition in the union, however was unsuccessful in achieving recognition for the female workers at this stage.

Agnes didn’t give up. In November 1943 her and fellow women members of the union led another strike which gained mass support amongst women workers across factories in the West of Scotland and lasted for over a month. Newspapers at the time reported over 2000 operatives at multiple factories were striking for Grade 3 wages: 37s, plus 20s, plus 13s 6d – the minimum rate for male machinists – from their Grade 4b (29s plus 22s) and 4a (34s plus 22s). According to the Liverpool Echo (3 November 1943) a court of inquiry had recommended an upgrading of women’s rates, and yet the proposed schedules of wages negotiated by unions and employers were not in line with expectations from women’s workers. On 19 December 1943 it was reported that only 12 members out of the 2000 on strike voted in favour of the union’s recommendation to resume working, with strikers saying they would continue until they got a definite offer from employers of equal pay for equal work.

The stalemate continued over Christmas, and in late December the strike committee asked MPs to intervene in reaching a settlement with the management of the Rolls-Royce factory. Another threat to production came from male employees would strike in sympathy if an agreement was not reached. At least 400 walked out on Friday 6 January 1944, increasing to 1000 over the next few working days. Finally, as pressure mounted, employers’ offered to honour the equal pay agreement and increase wages for women shop stewards. Agnes and the union’s battle against their employers shows how people’s power really can get results, despite the strike’s unpopularity due to it disrupting the war effort at the Rolls-Royce factory.

This time the strike was successful in getting the employers to honour the 1940 agreement. This was the only major strike over women’s pay during the war and was the first move towards equal pay legislation in the UK. Agnes remained employed there for 36 years mainly as a leading shop steward, until her retirement in 1973 at the age of 55 years old.

In a film ‘New Work for Women’, Agnes explained in her own words what happened during the strike:

“Employers were making a big bang oot us, they were making a bonanza oot of the exploitation of women at that time… We weren’e considering anything, except the fact that we were knocking oor pan oot and getting less wages of the guy next to us, that was the big battle.”

Agnes’ political activism didn’t stop at securing equal pay for women workers. In 1942 at the age of 24, Agnes joined the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPBG), She was on the CPBG Scottish Committee and then its National Committee. In 1954 Agnes was the first woman to serve as an executive on the AEU committee. In 1961 she visited the Soviet Union (Russia), and reported feeling impressed by the governance of the communist state. During this time, she was active in the peace movement and was arrested during a sit-in at the Polaris base at Holy Loch. She travelled as a World Federation of Trade Unions representative and was awarded the highest award that can be given to a normal activist the Gold Badge of the Trades Union Congress (TUC).

Sadly, Agnes passed away in Glasgow’s Southern General Hospital due to a stroke on 15th April 1994, aged 73 years old.

The demands of the Hillington strike continued in future strike actions by women such as the Dagenham strike in the summer of 1968 where nearly 200 women workers at the Ford Motor company plant walked out in protest against lower wages to men’s wages. This was followed by the Equal Pay Act of 1970, which makes it illegal to have separate pay scales for men and women based on their sex.