Like many neighbouring parishes, the origins of Linwood as a settlement can be traced back to the time of the Roman occupation.

In an attempt to prevent local tribespeople from cloaking themselves in the shadows of the trees and launching counterattacks, the Roman forces proceeded to cut down an area which is now known as Linwood Moss and serves as a crucial habitat for wildlife.

Following the invading army’s departure from the area, the lands which now constitute Linwood fell into the hands of the monks at nearby Paisley Abbey. During its time under their stewardship, the undeveloped area would be predominantly used for fishing the black cart and farming.

Centuries on, the name of the nearby Clippens House–which was built in 1817 by the Cochrane Family was derived from the tradition of the monks permitting the local people to cut or clip the surrounding fields.

Once the area’s agricultural uses began to dwindle, the area was redesignated as fertile ground for industry and soon, it would become a bustling hub of commerce.

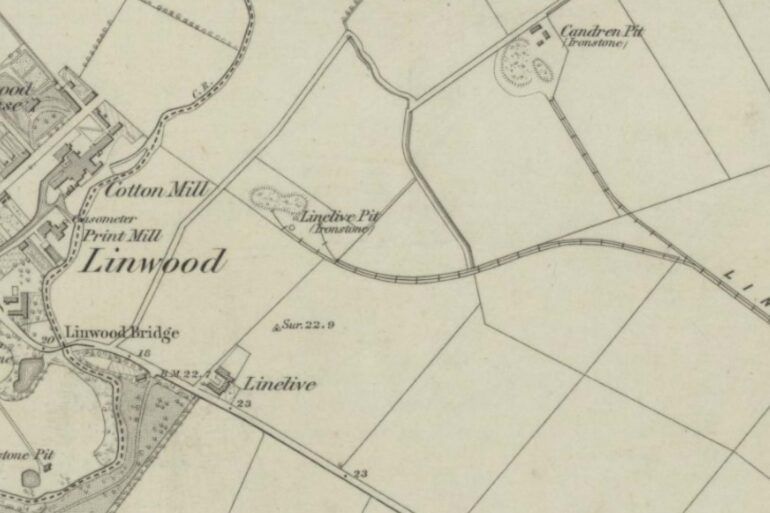

For an insight into how the area was viewed in days gone by, we need look no further than Francis Groome’s Ordnance Gazetteer Of Scotland. After he profiled the town between 1882-84, he proclaimed that “it arose from a large cotton-mill, built in 1792, burned down in 1802, and rebuilt in 1805; was laid out on a regular plan; is inhabited chiefly by the operatives of its cotton-mill, and by workers in neighbouring mines; acquired, in 1872, a water supply by pipes from the Paisley waterworks; and has an Established church, a public school, and a Roman Catholic chapel-school.”

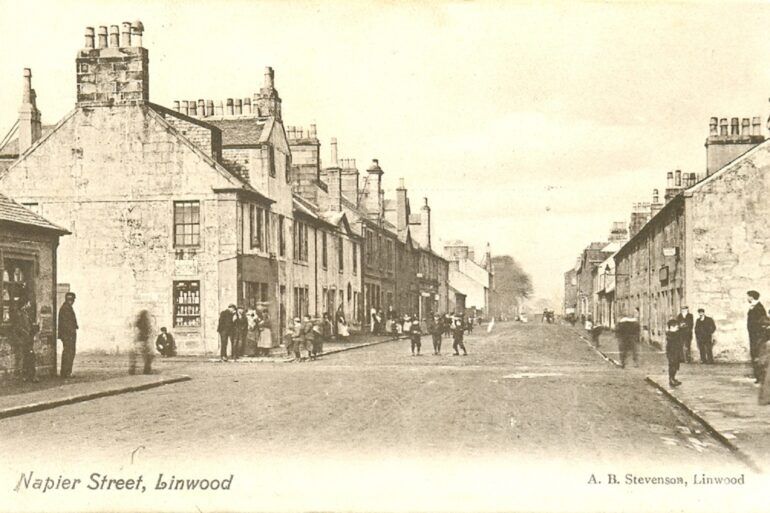

Initially composed of only two streets, Linwood’s expansion would directly correspond to the needs of the growing workforce. Founded by William Napier, James Kibble and Robert Orr along with his sons William and John and James Dunlop, the Linwood Cotton Spinning Company was the first major production line in the area and would derive its power from the nearby Black Cart Water.

As alluded to by Groome, operations were derailed by an accidental blaze. Afterwards, the mill– which was one of several in the area— was later owned by the Brown family, who were also the occupants of the nearby Linwood House. At its peak, the mill was one of the largest textile factories of the time in the country, employing over 400 local people and housing over 28,000 spindles across its six storeys until it closed in 1872.

Afterwards, their still viable premises were acquired by R&W Watson and repurposed as a paper mill which would keep production alive and well in Napier Street until it too closed its doors in the 20th century.

While Linwood’s lineage in the cotton industry is well documented, one largely unsung aspect of its history arises from its mining heritage. Led by James Anderson & Co’s Linwood Shale Oil Works, mining was a crucial part of the make-up of the area during the 19th century. In addition to several collieries in what was then widely known as “Linnwood”, the area’s storied history of mining also accounts for the existence of the Inkerman area. Situated on the Candren Road between modern-day Linwood and Ferguslie, this village, which took its name from a battle in the Crimean War, had seven coal mines alone and was home to over 699 residents who worked and lived in the area. By 1930, its school was demolished and the village wouldn’t be far behind. Soon after, it was absorbed into Linwood.

With the demise of both the cotton and oil industries in the region, it left a void for a central source of employment that would provide employment to those in Linwood and the surrounding areas. Thirty years on from Inkerman’s dissolution, Linwood would receive the driving force that it was looking for in the form of the Rootes Car Plant and associated Pressed Steel Factory.

Created after the company had noted the need for expansion and sought to use a designated development area in order to receive government funding, £23,000,000 was allocated to set up a factory in Linwood. Formally opened by The Duke Of Edinburgh in 1963, it would have a grand total of 5000 employees by Spring of that year.

A major production plant which would produce up to 40 vehicles an hour and utilised much of the workforce from the ailing shipbuilding industry, it was deemed to be such a major operation that British Railway manufactured a new train known as the “Imp Special” which would transport the completed Hillman Imps to down south.

A site of frequent industrial action from employees who vied for better working conditions, the plant would later come under the ownership of Chrysler and Talbot before eventually falling into the hands of Peugeot. After they’d purchased Chrysler’s UK operations, Peugeot evaluated the site and opted to close it down, leaving thousands out of a job in the process. Over time, the plant would be demolished and the last vestiges of the factory would be demolished in 1996.

An earth-shattering event for those in the area, its closure subsequently served as the inspiration for artistic homages to that era in not only The Proclaimers’ “Letter To America”, but Paul Coulter’s 2014 play “Linwood No More.”