Although not much is known about the site where a village eventually emerged during humanity’s more primitive days, the name “Kilbarchan” is believed to have been given to this invitingly rural area around 700 years ago. Derived from “the Church, Cell, or Retreat of Barchan”, it is named after Saint Barchan, an Irish priest who’d come to the area after venturing across the sea from Ireland and was said to have had the ability to deliver prophecies bestowed upon him after losing his sight.

With much of the land originally owned by the monks of the nearby Paisley Abbey, one notable change to its societal landscape came when an estate was founded in the area known as “The Barony of Auchinames.

Granted to Reginald Crawfurd by none other than Robert The Bruce in 1320, it was awarded to him and his family on account of the valour he displayed at the famed Battle Of Bannockburn and would become their ancestral base for hundreds of years. Shortly after receiving the barony , Auchinames Castle was soon built and belonged to the Crawfurd clan from the 14th century to the 18th when it was eventually demolished. Although it may no longer stand in all of its splendour, it is widely believed that disused dressed stones from the castle were used to build walls in the surrounding field. In addition, the last remnants of a chapel which was built by the Crawfurds– as well as a knight’s headstone– still survive.

Alongside this noble family, another early figurehead within the village was one Habbie Simpson, who would later enter the collective imagination of Scotland and the wider world through the poem ‘The Lament For Habbie Simpson’ by Robert Sempill.

While this may seem like a modest ode to a piper who’d passed away in 1620, this piece of work would go on to have wider significance than simply paying tribute to a local folk hero.

A popular poem which would be distributed far and wide, its metre– which, in layman’s terms, means its rhythmic structure– eventually became known within scribe circles as “standard Habbie” and would go on to be enlisted by the national bard himself, Robert Burns, on several occasions.

Venturing from the page to the place he called home, a statue of Habbie has stood in the steeple from 1932 through to modern times. During the annual Lilias Day celebrations– which is essentially the annual village festival– Habbie reanimates through another piper dressing up in his trademark garb and performing.

On account of the close affiliation that Kilbarchan feels with this historical figure its locals are colloquially known as “Habbies.”

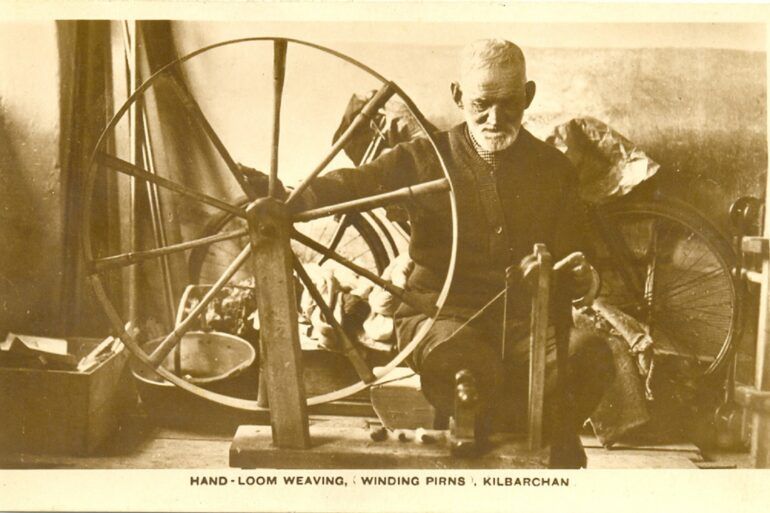

By 1695 it was estimated that there were around 40 weavers in the local area, although the poll tax of that year would suggest that agriculture remained the primary vocation of the local population.

Yet while cattle and crops had dominated the area for much of its history, the 18th century would become a time of widespread advancement for Kilbarchan.

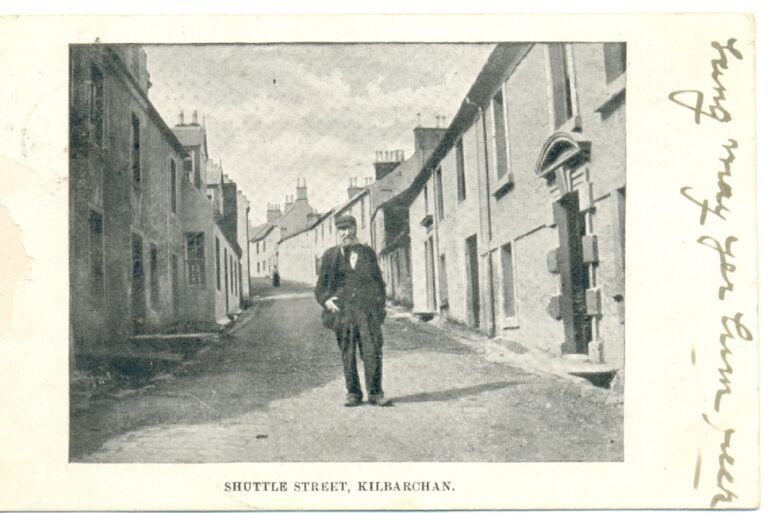

In step with many local areas, Renfrewshire’s well-documented affiliation with the textiles industry meant that Kilbarchan would soon build upon its small contingent of artisans to become a hotbed for both bleaching and weaving. In 1740- the village had a population of 200 that was split across 40 families. With the advent of Kilbarchan as a major settlement for weavers, this number would experience a further growth of 100 in the space of 30 years, with many residing in homes where the loom occupied the bottom floor while their living quarters were stationed above.

In addition to these domestic operations, Kilbarchan also played host to the first water-powered thread mill in Scotland. Commissioned by James Alexander in 1756, the mill, which was used as the site of his new invention which he claimed would “ go by water for twining thread”, was installed within a converted house and was made possible after Alexander received a grant of twenty pounds from the Board Of Trustees For Manufacture.

By the 1780’s, six bleachfields were situated in the area. Then, In 1793, John Barbour, founder of the firms Barbour and Duncan/Barbour and Howie, began exporting muslin and linen products from his factory in Kilbarchan to Ireland.

Although there was once plans in motion to construct a large steam-powered cotton mill in 1825, this ultimately never materialised and by consequence, Kilbarchan is a rare exception within Renfrewshire where these massive operations were at the forefront of many towns and other localities. For the most part, Kilbarchan’s weavers were self-employed and worked on a contract basis with manufacturing houses in neighbouring Paisley and Glasgow.

By the end of 1840, there were as many as 900 hand looms within the boundaries of the village but as the technology and skills grew outmoded in the fact of mass production, this number would decline to just 120 by the time that the 20th century was ushered in.

Despite the fact that the industry itself may have been all but abolished, its influence is still felt to this day and many residences in the area were converted from the foundations of original weaver’s cottages. In addition, one loom has been preserved in its original location as a local tourist attraction, giving visitors a vivid and immersive insight into the life of a Kilbarchan local as they spent their working days painstakingly weaving from within their very own homes.